We are trained to see nuance and complexity. Academics are skeptical of overly simplistic theories, and we are methodical and careful before hazarding a generalized claim.

Except, of course, when it comes to the finances of our own institutions.

Overgeneralization about university budget stuff is a whole genre. Perhaps the one I hear the most is, “The university budget is screwed up because administrative bloat. We just have too many deans and associate deans and AVPs they’re all overpaid.” I do think there’s a lot of complexity there, and that’s for another time.

The one I want to discuss today goes like this:

Universities (at least in the US) are a money making business whose principal income is government grants. All incentives for departments are to get their faculty to bring in as much grant money as possible. That’s the only thing that matters ultimately.

That’s was quote from some guy on a social media site (which I’m choosing to not attribute because I don’t want to make this about him.) I picked it because it seems to be a good encapsulation of some conventional wisdom in the sciences.

And it’s (mostly) factually incorrect.

Even in major research universities1 that have stratospheric expectations of external funding from tenure-track science faculty, this is still just not what goes on in the university.

What’s the deal with this common misconception and how important is the overhead that we bring in on grants?

I’ve heard it said on a bunch of occasions that faculty are expected to bring in grants with indirect costs because they need to cover the cost of supporting their research programs. But even PIs in highly successful laboratories2 aren’t even close to bringing in enough IDCs (indirect costs, also sometimes called overhead) to pay for the full cost of running their labs and the associated services to keep the place running. The cost of running our labs (salary for the PI costs, plus the cost of the graduate students in the lab, research space, administrative support, safety, hazardous waste disposal, facilities, utilities, wifi, and all that other stuff, not to mention startup) is simply going to exceed whatever we bring in. In a lot of productive labs, the amount of overhead generated each year wouldn’t even cover the full salary and benefits of the PI!

When universities spend money on research, it costs them more money to support the work than just the indirect costs that they receive.

Why are universities taking money from their budgets to support our research? Because that’s what universities do! Research is part of the institutional mission. The more and better research that happens, the higher prestige of the university, the easier it is to attract donors, the higher the rankings, and so on. It’s in the university’s interest for us to do research, and indeed the place is designed to support it, even though our grants don’t support the full cost of the work. I think a lot of folks haven’t who seen the budget ledgers at their institutions haven’t been able to appreciate the actual factualness of this reality.

So if our research grants aren’t enough to pay for our research, where does the money come from? Education. How does that work?

Well, after saying that generalizations are bad, I’m now going have a go at one: Research universities are designed to launder funding received for undergraduate education and apply it to research mission of the institution.

From the accountant’s perspective, graduate students are the highly efficient tools used to convert undergraduate education funding into research activity.

Let me walk you through this reasoning.

To explore this education-funds-research model of universities, one big giveaway is how grad students are funded and what they do with their time. It goes almost without saying that the energy fueling research universities comes from the PhD students who spend several years creating the research product that drives institutional success.

When grad students are funded through teaching assistantships, they receive low wages and are expected to teach with maybe half of their time, and they are expected to spend the rest of their time doing research while not being paid to do that work at all. This research greatly benefits the institution and the PI in a variety of ways, but is not compensated because it’s training that actually costs students money, though often the university is kind enough to waive that tuition in a cute bit of fiction that grad students are not really laborers. (Except when they are, of course, which is when it saves the institution some money.). The economics of the situation are simply reduced the reality that grad students are paid a very low wage to teach a relatively large number of undergraduates. Hiring graduate students to teach undergraduates is a huge bargain for the university, as they are getting huge amounts of research out of these people and yet are only paying them to be in the classroom with undergraduates. If universities didn’t have graduate students working for so cheap with the expectation of a credential of a PhD after those years of labor, then the whole thing would fall apart. (Which is why grad student unionization is broadly taking off.)

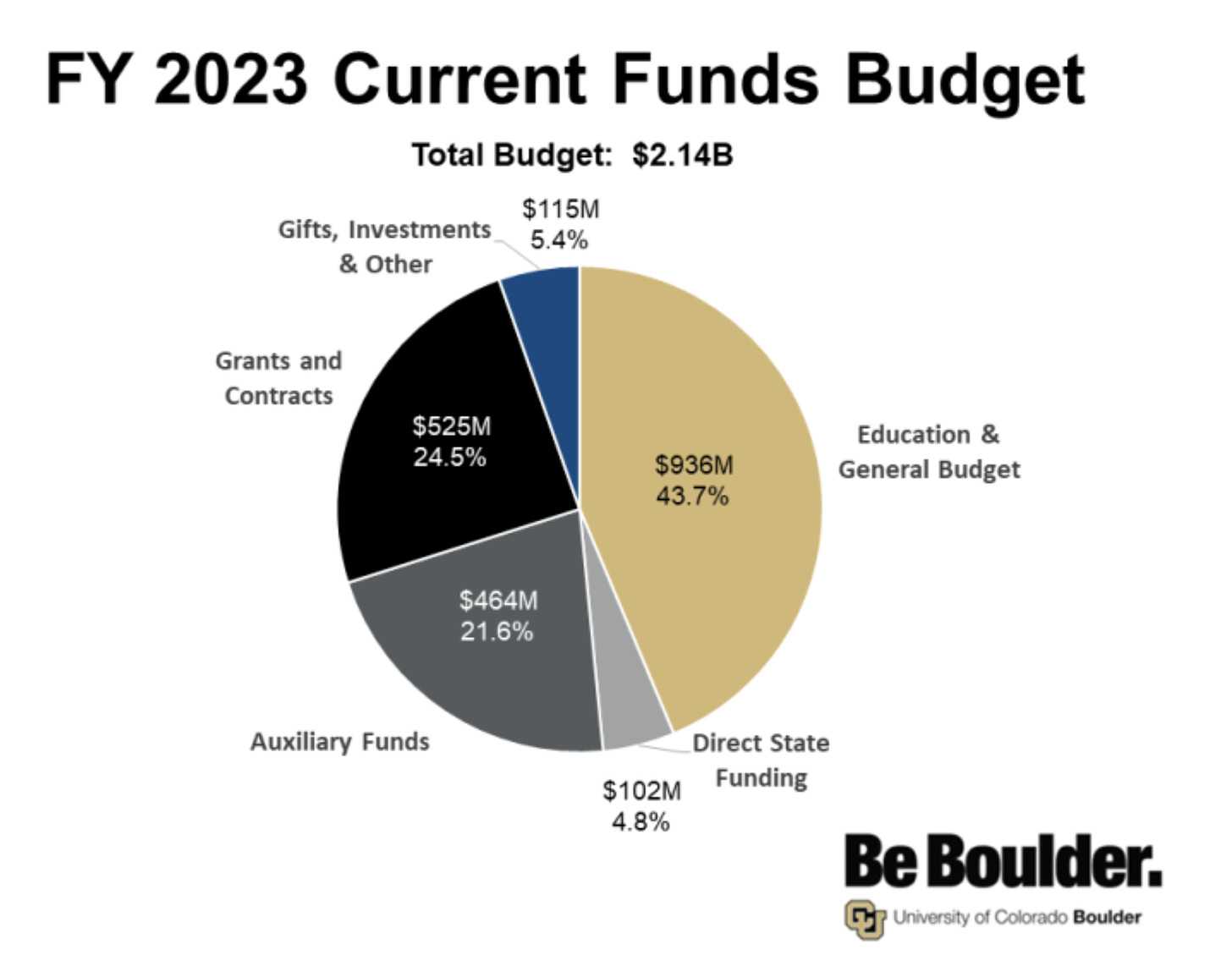

Now let’s look at where the money for universities comes from. Large research universities that have sizable undergraduate populations are collecting more money to teach than they are to do research. In public universities, the combination of tuition from students and state educational funding typically exceeds research, and in private universities, it’s just tuition alone. Don’t just take my word for it. And here’s the University of Colorado as one example to share, which I haphazardly picked because that’s where I did my PhD.

Here’s another comparison to understand how education funding is channelled towards research support. In California, there are stark differences between our two systems of 4-year universities. The UC system was designed to be research institutions, and the CSU system was designed to primarily educate undergraduates. While the fraction of funding that we get from the state has tragically waned over the decades, we still get a bunch of money from the state of California. (Students in the CSU system used to have no tuition whatsoever.3)

The CSU system enrolls more than double the number of undergraduates as the UC system, and the tuition charged by the UC is way higher than in the CSU. Both systems get roughly the same amount of money from the state. You might expect as an an undergraduate, you might expect all of that money and lower undergrad enrollment to result in greater investment into education, right? Nope. The CSU pours its resources into undergraduate teaching and it shows: in class sizes, workload expectations of faculty, how much they pay non-tenure track instructors, and so on. The bottom line is that the undergraduate education in the CSU is better than in the UC and I’ve yet to meet a single person who has directly familiarity with both systems who would ever disagree with that. (But of course, a degree from the UC opens more doors than one from the CSU, but that’s independent of the quality of the education).

The UC has undergrad lectures with several hundred students, and the real interactions with students often happens with poorly compensated graduate students. There are fewer opportunities for hands-on laboratories in the UC, and the CSU is where students work more closely with professors. So why is the UC education more expensive when you get less for your dollar? The answer is that all of that funding for education doesn’t go to undergraduate teaching. It goes to fund the research mission. When the university is paying grad students to teach undergrads, what they’re essentially doing is using money received for teaching and channeling it into senior authorship for PIs and increased research productivity by the institution. So what that means is that tuition is paying for a more prestigious university, which is ultimately what many undergrads are looking for.

I’ve now made the case that overhead isn’t the biggest piece of the university budget, that it doesn’t even cover the cost of running one’s research lab, and that big universities take education funding to support research.

But isn’t overhead still important? Yes, oh yes, it is, at least in the lived experiences of science faculty. When universities are putting high pressure on faculty to bring in overhead, I think there are two main factors at play:

Funds from indirect cost recovery have few strings attached, so there is much more flexibility in spending4.

While to some extent universities have grown to rely on and expect a certain amount of returned indirect from faculty grants, bringing in additional overhead is gravy. The reason that universities pressure faculty to bring in overhead is not because these funds are not essential, they pay for the good extras that lubricate the machinery of the research enterprise.

What are some of these good stuff that are not essential? A funded seminar series, travel support, equipment service contracts, well-catered department retreats, vans for field trips, grad student recruitment weekends, reassigned time from teaching, and such.

If someone is telling you that you need to bring in a certain amount of IDCs to pay for the cost of keeping you employed, that’s straight up gaslighting. Because what’s keeping you employed is all of those undergraduates roaming around your campus. They might be in your way but they’re the ones paying your bills. Even if you’re bringing in a huge amount of indirect, keep in mind that that same amount of money could be covered by a relatively small number of undergraduates. And your salary, lab space, and all that, the IDCs might pitch into that to some extent but your grants aren’t what’s keeping the lights on and paying the rent. It’s what you and grad students are doing in the classroom that pays the bills.

If universities were expecting research to cover the cost of having you on board, then what they’d do is make sure that you pay your own salary out of your grants, and indeed, that is exactly what happens at many biomedical research centers that don't do the undergrad education thing. There’s a whole thing where you can have a full professor position but the salary is all soft money, meaning you only get paid if you get paid out of a grant.

Yes, universities with big research infrastructure have built that structure in part based on indirect costs from grants. And yes, universities need faculty to bring in grant dollars to sustain that infrastructure. But are universities expecting you to bring in enough overhead to cover the cost of paying you and running your lab? Heck no. That’s why there are undergraduates, to bring in the money. And that’s why graduate students are there to teach them!

Is there a problem with this funding model, is it exploitative and harmful to students, and does it produce perverse incentives? Oh, yes it does.

I’m talking about traditional universities, not medical research centers or other places that don’t enroll substantial numbers of undergrads. Places like MIT and CalTech don’t fit this description, but flagship public universities as well as major private universities do. To some extent, few campuses that have astronomically dizzying endowments are a whole separate thing. Nonetheless, even at a place like Harvard, the dollars brought in from teaching exceed the dollars brought in from research. It’s just that the endowment and donations from wealthy folks exceeds either one of those!

Again, I’m not talking about biomedical research centers or high specialized research institutes. I’m talking about typical science departments in R1s that also are in the business of enrolling a lot of undergrads.

Arguably, all of that investment into public education decades ago is why California is the 4th largest economy in the world, we just passed Germany, or something like that.

Case in point: the last time I did a campus visit in which a variety of people ate out and drank a decent amount of booze, all of the booze was paid for from a separate account, and I’ll bet you that it was returned indirect.