Last week, I was at a workshop and a fellow participant made an observation that really caught our attention. They explained:

In universities, faculty usually have three types of duties: “scholarship,” “teaching,” and “service.” In their national lab, the job doesn’t include service. Instead, all of the stuff that we would call service, they call “leadership.”

Service is a bad thing. Leadership is a good thing. But what is the difference between university service and university leadership? Maybe if we called it “leadership” instead of “service,” it might be perceived as something more valuable and worthwhile.

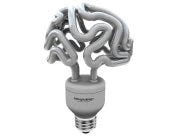

At moment, at least for me, a cranial lightbulb turned on.

I mentally catalogued my recent “service,” on campus and off campus. Chair of department RTP committee; university senate; department graduate committee; some other committees; mentoring junior faculty; K-12 teaching advisor; subject editor and associate editor for academic journals; reviews for manuscripts, grants, and tenure files; a couple committees for professional societies.

A lot of these things are leadership roles, or at the very least, an opportunity to exercise leadership and get things done right. Viewed as “service,” this work is undesirable, but “leadership,” is a chance to create a positive impact for the community.

In the university, we see service as a thing we have to do, not a thing we want to do. Some folks think of service like a chore, like, say, having to do dishes at home. Nobody wants to do dishes, it’s not necessarily pleasant, and we do it mostly because if we don’t, then conditions will become disgusting.

Is it possible to think of doing dishes at home as a form of leadership? Well, I think so, at least for the other members of the household. As a parent, then doing basic housekeeping sets a strong example, and as kids grow to the point where they can take responsibility for the dishes, then this is contingent on our leadership. Moreover, when someone does the dishes, that means someone else is not doing the dishes. Failing to do the dishes at home — especially for dudes who on average do them less — is a failure of leadership. At our universities, our women colleagues “do more dishes” than the men. This is also a failure of leadership by the men in these departments. Some leadership opportunities provide more opportunity for advancement, and these need to be distributed equitably.

As for the least desirable item on my list of service — representing my department in the University Senate — there are two ways I can view this as leadership. The more obvious one is that have the opportunity to set the course of policy-making on campus (for reals). If I really want our university’s administration to address some particular issue, I can work towards making that happen. There’s a second way that serving on Senate is a form of leadership. It’s clear that none of the faculty in my apartment want to do this — it’s seen as a pretty big time suck and a source of annoyance. (I can’t disagree with that, either.) By agreeing to do this, that means I’m protecting junior faculty from this role, and freeing up my other colleagues to focus their service leadership in roles where they feel they can be more effective.

If I try to think of the most menial service task that I do at my university — one that couldn’t construed as leadership –I come up empty. Now I’m trying to think of any kind of role that any faculty are filling and, yeah, I’m still coming up empty. Even things like Assessment Coordinator and College Space Allocation Committee or whatnot — those have ways to make a difference in making the community better. A bad “service” assignment is one that requires a lot of effort but has little visible consequence. That’s also bad leadership assignment, too.

I’m not sure in what way academic service is not academic leadership.

I suppose if we were to relabel “service” as “leadership” across my campus, some folks would complain this is a form of newspeak, but I think it would be a wholly appropriate label. Do any universities do this? Do any national labs not do this? I suspect we all might benefit from at least seeing it this way.

Terry, I somehow missed this when you first posted it. (I may not have even known to follow your blog back in 2017!) But, it resonates DEEPLY with me right now! I'm in the middle of a multi-year audit and overhaul of the volunteering work I do in and beyond academia. I've been an "over-committed" service-leadership person since I was a kid, and the fact that there's actually a job description slot for it in academia has probably compounded the challenge for me. Actually documenting what I do (including time-tracking) has helped a lot, as has a dedicated process of goal setting (and regularly revisiting those goals) and then comparing the time spent to my stated goals. It's all helping me refine how I spend my time in ways that have helped me to feel a great deal more satisfaction in what I do at and beyond work. (I have written up some of the stages of this whole process on my blog, along with a lot of citations about the imbalance of who does academic service, etc. I'll link to that here in case these tools are helpful for anyone else: https://www.commnatural.com/blog/tags/no-for-it.) But, there's one thing that I would add to the "service is actually leadership" reframe. That is, we need collective and especially administratively managed accountability. Calling service leadership will just be a euphemism if the same people keep opting out of their responsibility to the collective good.